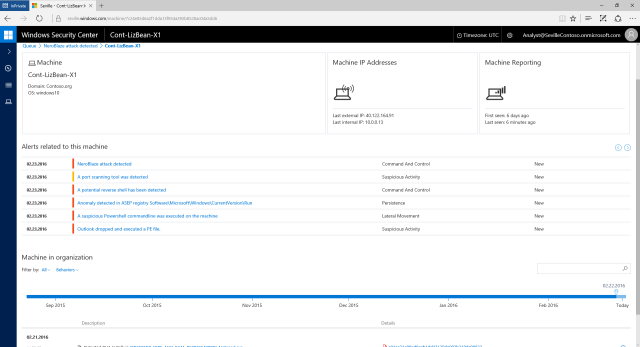

WDATP can detect anomalous behavior even when the malware scanner doesn't find anything wrong. (credit: Microsoft)

Microsoft is beefing up Windows Defender, the anti-malware program that ships with Windows 10, to give it the power to tell companies that they've been hacked after it has happened.

Attacks that depend on social engineering rather than software flaws, as well as those taking advantage of unpatched zero-day vulnerabilities, can evade traditional anti-malware software. Microsoft says that there were thousands of such attacks in 2015, and that on average they took 200 days to detect, and a further 80 days to contain, giving attackers ample time to steal data, and incurring average costs of $12 million per incident. The catchily named Windows Defender Advanced Threat Protection is designed to detect this kind of attack, not by looking for specific pieces of malware, but rather by detecting system activity that looks out of the ordinary.

For example, a social engineering attack might encourage a victim to run a program that was attached to an e-mail, or execute a suspicious looking PowerShell command. The Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) software that's typically used in such attacks may scan ports, connect to network shares to look for data to steal, or to remote systems to seek new instructions and exfiltrate data. Windows Defender Advanced Threat Protection can monitor this behavior and see how it deviates from normal, expected system behavior. The baseline is the aggregate behavior collected anonymously from more than 1 billion Windows systems. If systems on your network start doing something that the "average Windows machine" doesn't, WDATP will alert you.